PMT: Before The Market Catches On: Free Release

This article was originally posted for paid members of our service on October 5th, 2023. There are a few updates I need to reference.

Prices have increased since then:

- PMT-A (PMT-A) up 4.4% ($21.79 today)

- PMT-B (PMT-B) up 6.6% ($21.41 today)

- PMT-C (PMT-C) up 2.6% ($17.50 today)

Since the original publication, TWO-A and TWO-B were also confirmed as floating based on SOFR.

Aside from those adjustments, I believe the rest of the article is still relevant. I will preface it by reminding investors that this is my opinion; I am not a lawyer or a judge. I never went to law school. I am simply sharing my views on the matter. Decisions by CIM and TWO have been in line with my interpretation.

Original Article Summary

- PMT claimed they would turn their fixed-to-floating shares into fixed-to-fixed shares. They were woefully unprepared.

- CIM already came out supporting our interpretation of a very similar prospectus with CIM-B. TWO is keeping quiet but will probably follow PMT.

- There are three categories for LIBOR contracts under the rules from the Federal Reserve Board. We can tell where PMT should land, which tells us which rules apply to them.

- Voices arguing that PMT is right have failed to provide any meaningful evidence for their position. The evidence is overwhelming. It all supports floating rates.

- Regardless of which path we follow for PMT, it ends in their defeat. The only chance I see for them to remain fixed is to avoid having any judge or regulator inspect their decision.

Article Starts

One of my ongoing projects has been evaluating the risk/reward profiles for the preferred shares. To that end, I’ve continued to look into shares where there is greater uncertainty about the future status. These are shares that should be “fixed-to-floating”, but management is (or was) interested in finding ways to keep the shares at a fixed-rate dividend.

Specifically, we’re talking about:

PMT-A (PMT.PA) (PMT.PR.A)

PMT-B (PMT.PB) (PMT.PR.B)

CIM-B (CIM.PB) (CIM.PR.B) (now confirmed as Fixed-to-Floating)

TWO-A (TWO.PA) (TWO.PR.A)

TWO-B (TWO.PB) (TWO.PR.B)

It’s the first 3 shares that really have my attention. The preferred shares from Two Harbors (TWO) are part of the group but less interesting to me as the floating dates are so far away.

Note: If we cover a share and it isn’t in that list, we’ve already determined that this specific risk doesn’t appear to be relevant to those shares.

Note 2: This article was started before the CIM-B announcement. The article is big and deep. I apologize for the length. My first goal is precision. Being concise comes secondary.

Disclosure

I’ve already prepared several articles on the shares. However, I keep coming back to the logic. My views have changed some, but not all that much. As a reminder, I am not a lawyer or a judge. I have never practiced law nor studied law in a structured setting. I am simply an analyst looking at the terms of investments. This article only expresses my opinion.

Chimera Investment (CIM) validated much of the work in this article. They validated it by filing the 8-k for CIM-B. Specifically, the 8-k indicated that CIM-B was already automatically transitioning to using SOFR + the spread adjustment.

Almost The Same

There are two sources I’m using to determine the rules.

The United States government posted the law according to house.gov.

Note: Cornell also hosts a version of the law, but I find the document from house.gov easier to navigate.

The Federal Reserve posted the final rule: Regulations Implementing the Adjustable Interest Rate (LIBOR) Act.

In theory, these two should indicate the exact same thing. Any differences would just be clarifications providing greater detail. In practice, the wording may be different. That can be a problem.

You can verify that there are flaws by going to the “sources” section in the Federal Reserve’s final rule. Many of the links are broken. They relied on directing links through govinfo.gov. Unfortunately, that site doesn’t work well (if at all).

There are other issues as well. I will go to great lengths to point some of them out.

Both Valid Sources

I believe courts will have the right to enforce any clause from either source.

Defining some terms:

- “The law” refers to the first source, written by Congress.

- “The regulation” or “the rule” refers to the second source, written by the Federal Reserve.

A Moment to Complain

I strive to transmit information clearly. The information I transmit may be positive or negative. However, it must be clear. This standard should be applied more frequently. It would dramatically simplify reading the law. More transparent laws should be a goal (but it doesn’t appear to be).

This job (reviewing the law) could’ve been much easier if anyone involved had committed to the following ideas:

- Tables are better than walls of text.

- Sentences with more than 2 commas are bad.

- No document should be published with more commas than periods.

Ernest Hemingway was an author. He won the Nobel Prize in literature. He wrote books with an average of just over 10 words per sentence. Short sentences reduce confusion. They are particularly important for complex topics and large amounts of money.

Complexity compounds. When we have differences between the law and the regulations, those long sentences become even worse.

I believe that PennyMac Mortgage Trust (PMT) misunderstood the law. I believe better writing could have prevented that confusion.

Three Categories

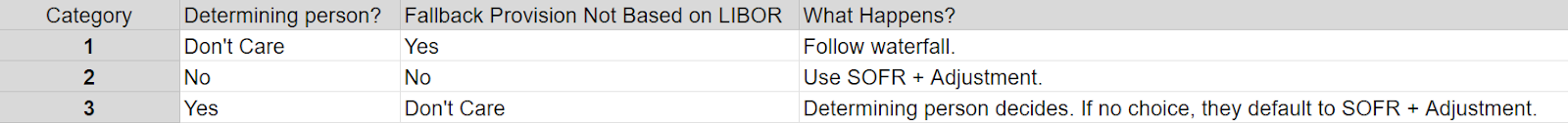

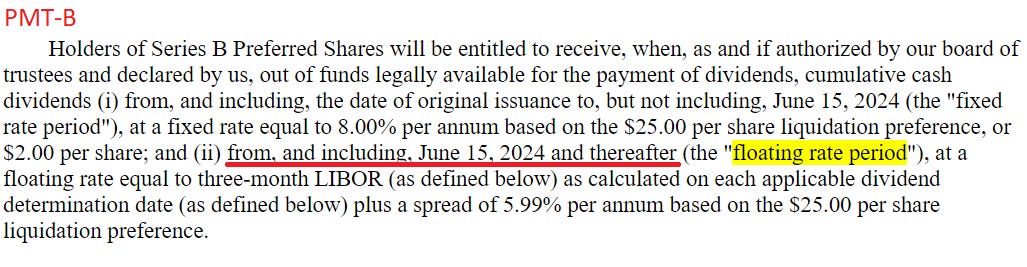

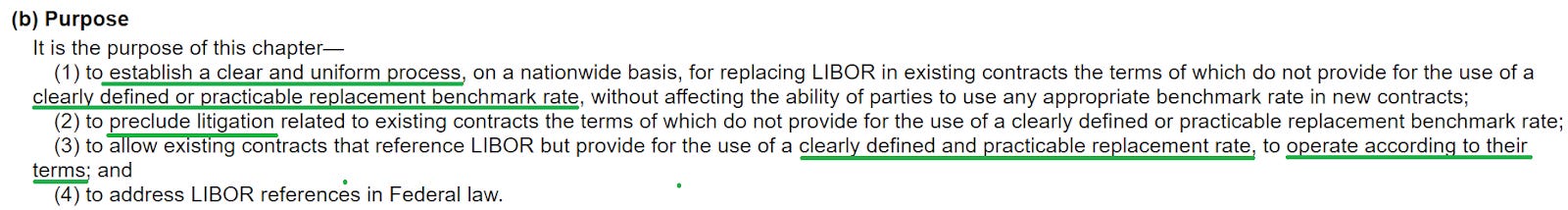

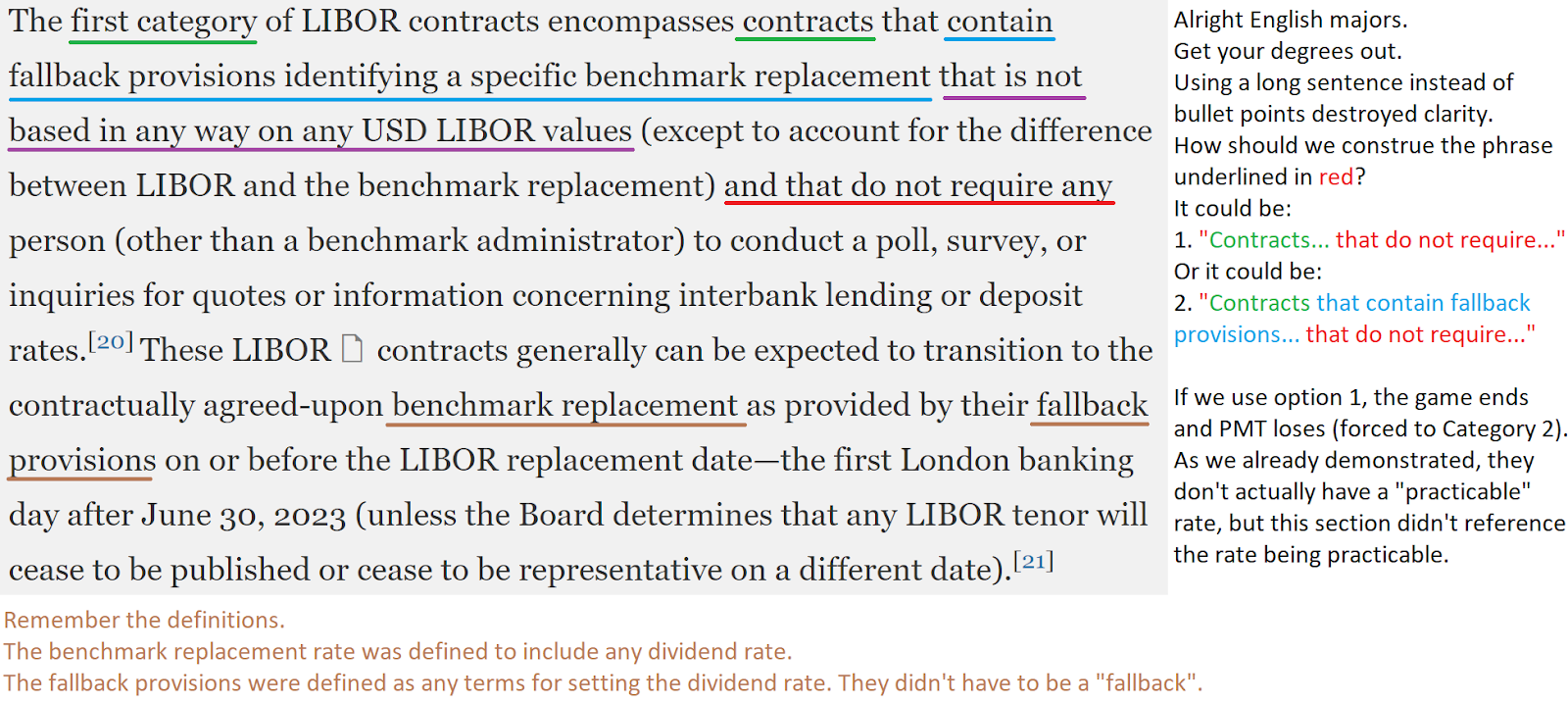

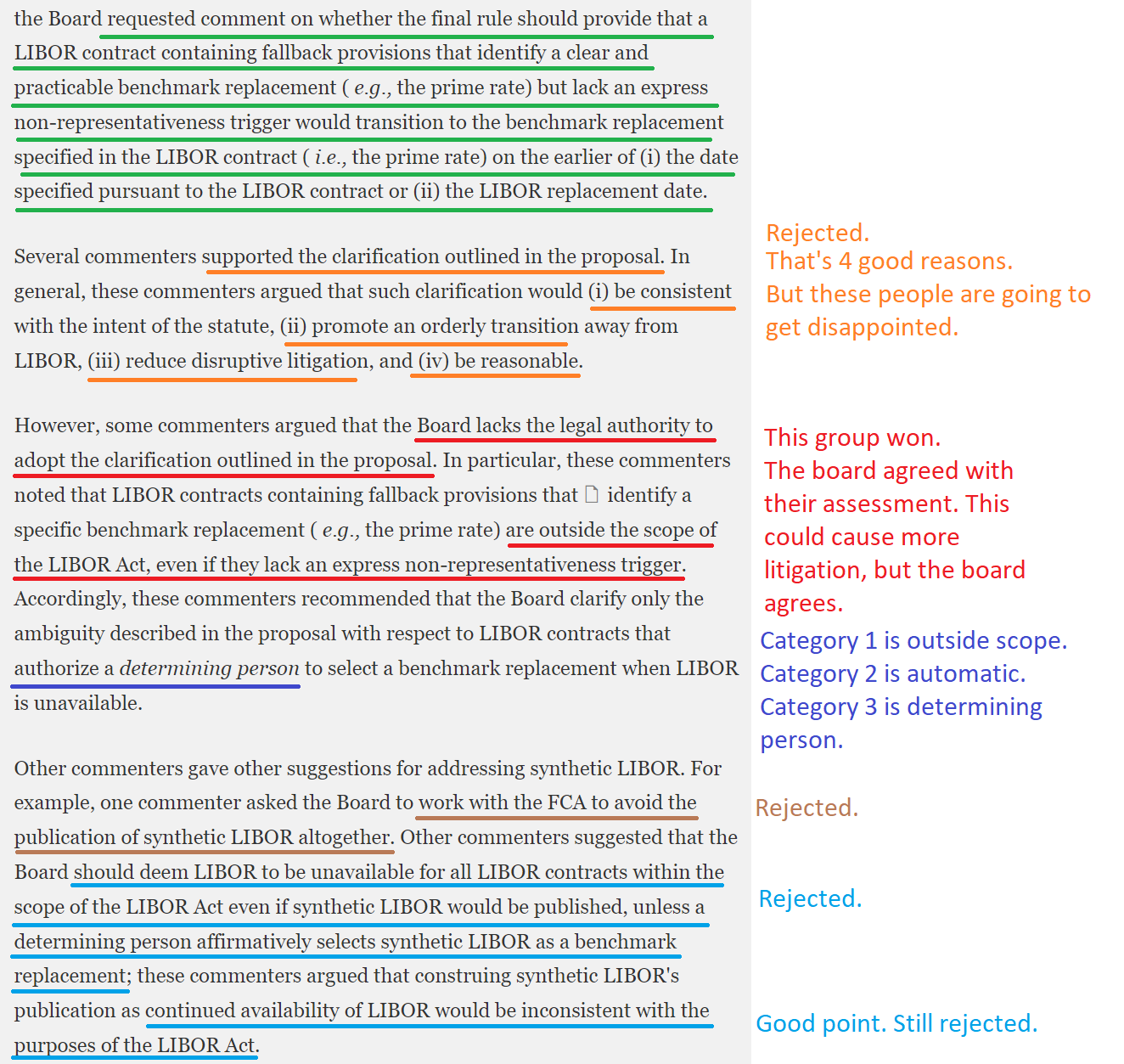

The Federal Reserve decided: “The LIBOR Act broadly distinguishes between three categories of LIBOR contracts with different types of fallback provisions.”

This concept of “three categories” simplifies the process. Since they are part of the regulation (though not in the law), we will use them.

Here’s a quick table for easy reference:

Note: The “Fallback Provision Not Based on LIBOR” will get more nuanced. This will be critical.

This table covers all possible scenarios. However, they are not mutually exclusive. A contract might have:

- A Determining Person AND

- A non-LIBOR option

That contract would fit in categories 1 or 3. Thankfully, that doesn’t appear to be an issue for the shares we cover. It appears that the rule is probably intended to slot the contract into the first category that matches them, but this wasn’t clarified properly.

Note: It would’ve been better to create a fourth category and make them mutually exclusive. Even if the outcome were identical between the two categories, it would make the process quicker by reducing the potential for conflict.

For our purposes, the “contract” and the “shares” are the same. Each share has a specific contract (in the prospectus). The share and contract cannot be separated. Therefore, the share falls into whichever category the contract falls into.

Note: This article comes in at over 4,300 words, not including those in images. The rest is going to be behind the paywall.

The Argument

We want to be able to assign a category to each share. If we know the category, we can use the chart to determine the intended outcome.

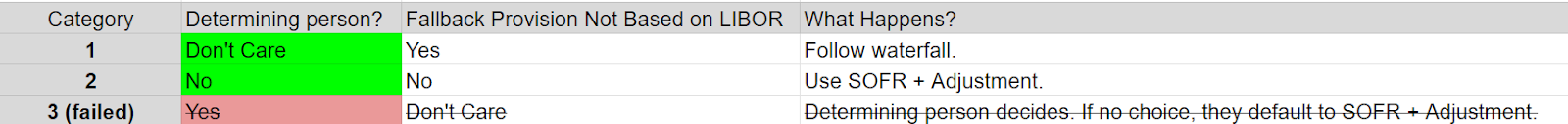

The 5 mortgage REIT shares we are looking at do not have a determining person.

Therefore, Category 3 is not possible for these shares.

Now we can update the table for categories:

Since Category 3 won’t work, they must be Category 1 or Category 2.

This is the disagreement:

- PMT’s fixed-rate statement implies they are Category 1.

- I believe they are Category 2.

- CIM’s 8-k filing implies that CIM-B is Category 2 because it references “the applicability of the Act” and “will automatically replace three-month LIBOR”.

Spoiler: Even if PMT could get Category 1, I believe they would still lose. This article is a walkthrough on how PMT loses the case in any scenario in which they are challenged. PMT’s only hope, in my opinion, would be that everyone remains silent.

Benchmark Replacement and Fallback Provisions Defined

The LIBOR Act defined several terms. A few of those definitions are at odds with the interpretation most people might get from reading the term. They are important, so I’m including them.

Benchmark replacement: The term "benchmark replacement" means a benchmark, or an interest rate or dividend rate (which may or may not be based in whole or in part on a prior setting of LIBOR), to replace LIBOR or any interest rate or dividend rate based on LIBOR, whether on a temporary, permanent, or indefinite basis, under or with respect to a LIBOR contract.

Fallback Provisions: The term "fallback provisions" means terms in a LIBOR contract for determining a benchmark replacement, including any terms relating to the date on which the benchmark replacement becomes effective.

There are two key points I want to make here:

- The “benchmark replacement” is not limited to actual benchmarks. It can be any interest rate or dividend rate. Therefore, investors shouldn’t get caught up in the idea of actual benchmarks.

- The term “fallback provisions” doesn’t require it to be a backup. The very first option for setting the dividend is still a “fallback provision” because it is one of the terms in a LIBOR contract for determining the dividend rate (referred to as benchmark replacement). Therefore, all methods of reaching a dividend rate fall within the category of “fallback provisions”.

Do Shares Have a Non-LIBOR Fallback Provision?

Technically, these shares have a fallback provision that is not based on LIBOR.

For shares that are not yet floating, the “immediately preceding dividend period” would be a non-LIBOR value. Based on this fact, management would like to claim Category 1 and declare that the dividend will never change.

Case closed? Not at all.

Let’s Get Practicable

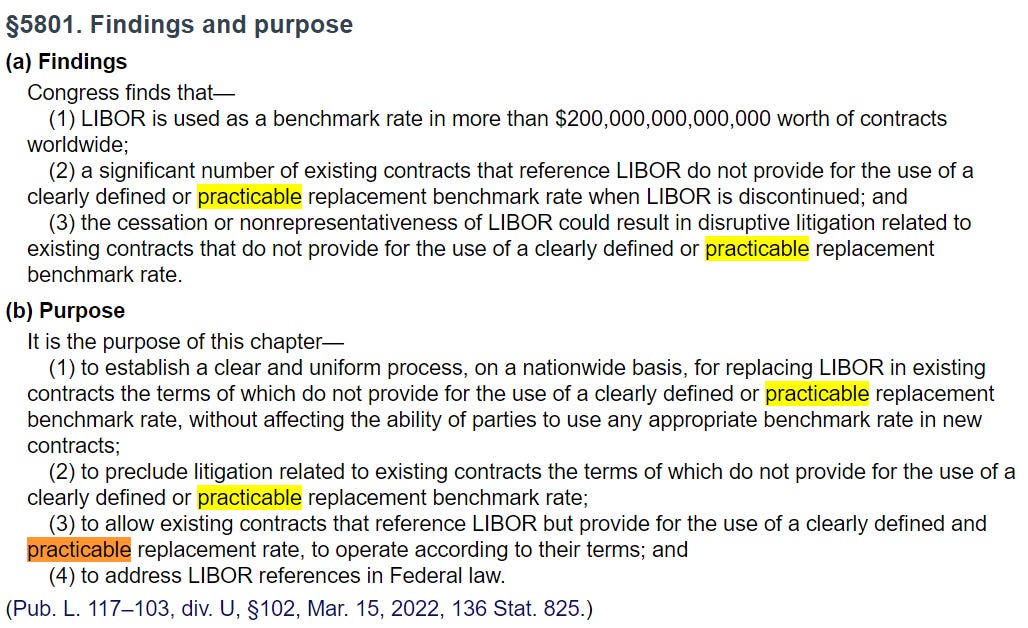

The word “practicable” (which means “able to be used” or “useful”) is about to become very important.

The law issued by Congress uses the word exactly 5 times:

The fifth (in orange) is the most important. The Federal Reserve took that purpose seriously.

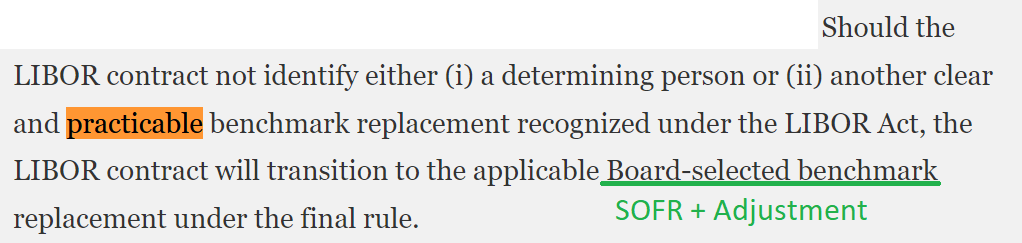

The word “practicable” comes up 18 times in their rule. They specifically take aim at any “benchmark replacement” that is not practicable:

This sentence clearly indicates that if the LIBOR contract has neither a determining person nor a practicable benchmark replacement, it will land in Category 2. This is an important difference. A benchmark replacement that cannot be used (not practicable) is not acceptable. They reference this repeatedly throughout the rule.

Layout

I prepared this argument before finding a proper voice for the other side of the argument. Consequently, I went about disproving all arguments. It turns out some fixed-rate proponents actually took the simplest and most absurd path.

Dividend Periods Defined

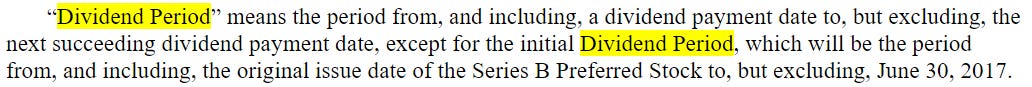

If you saw my prior work, you may remember the definition of a “Dividend Period”. Here’s a refresher:

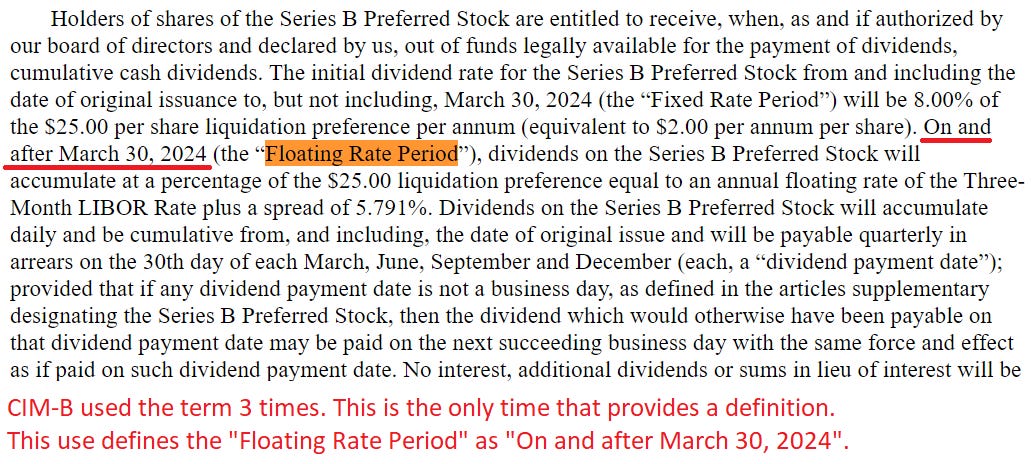

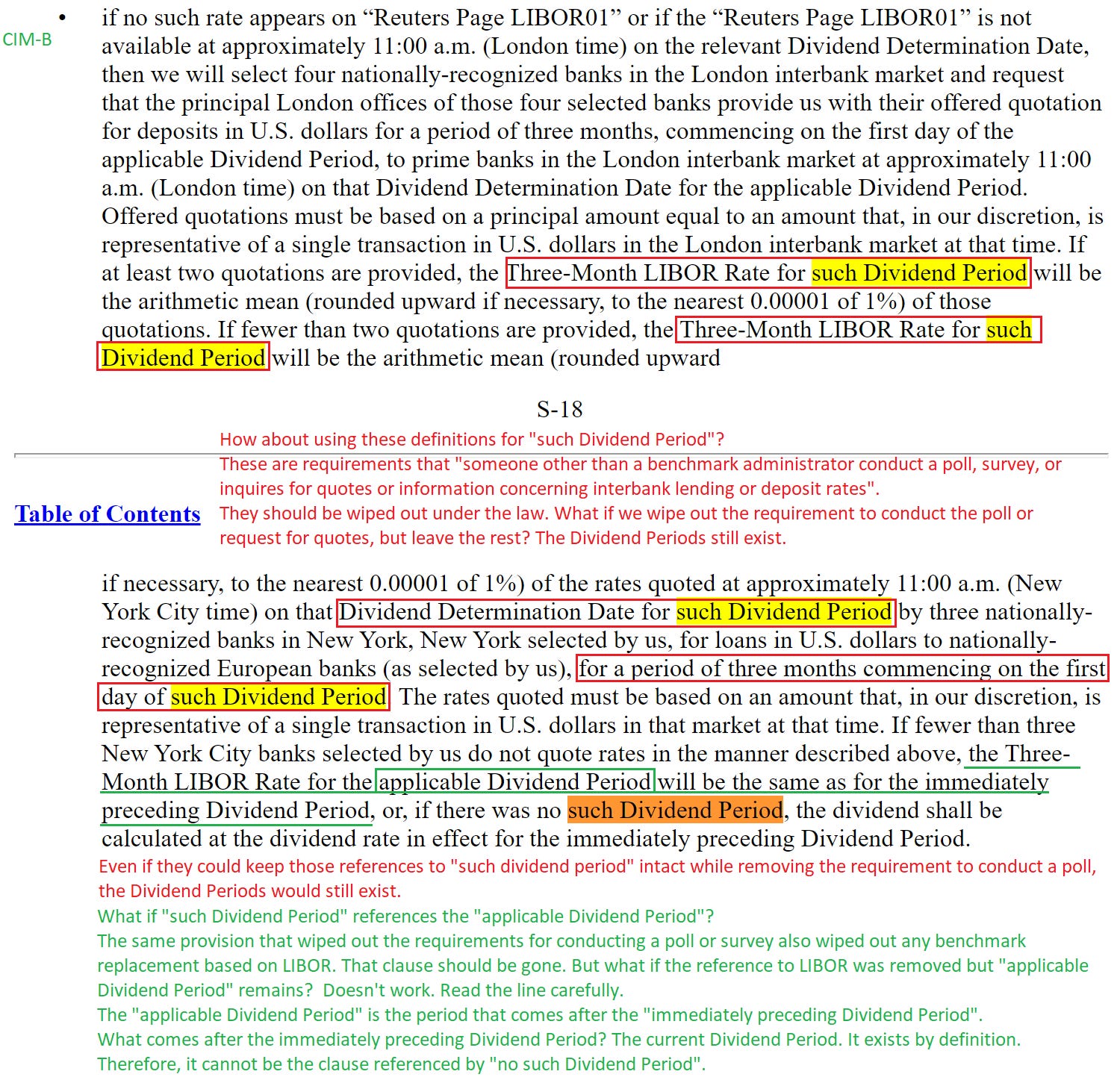

For CIM-B (now confirmed as fixed-to-floating):

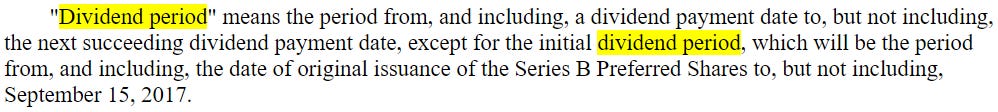

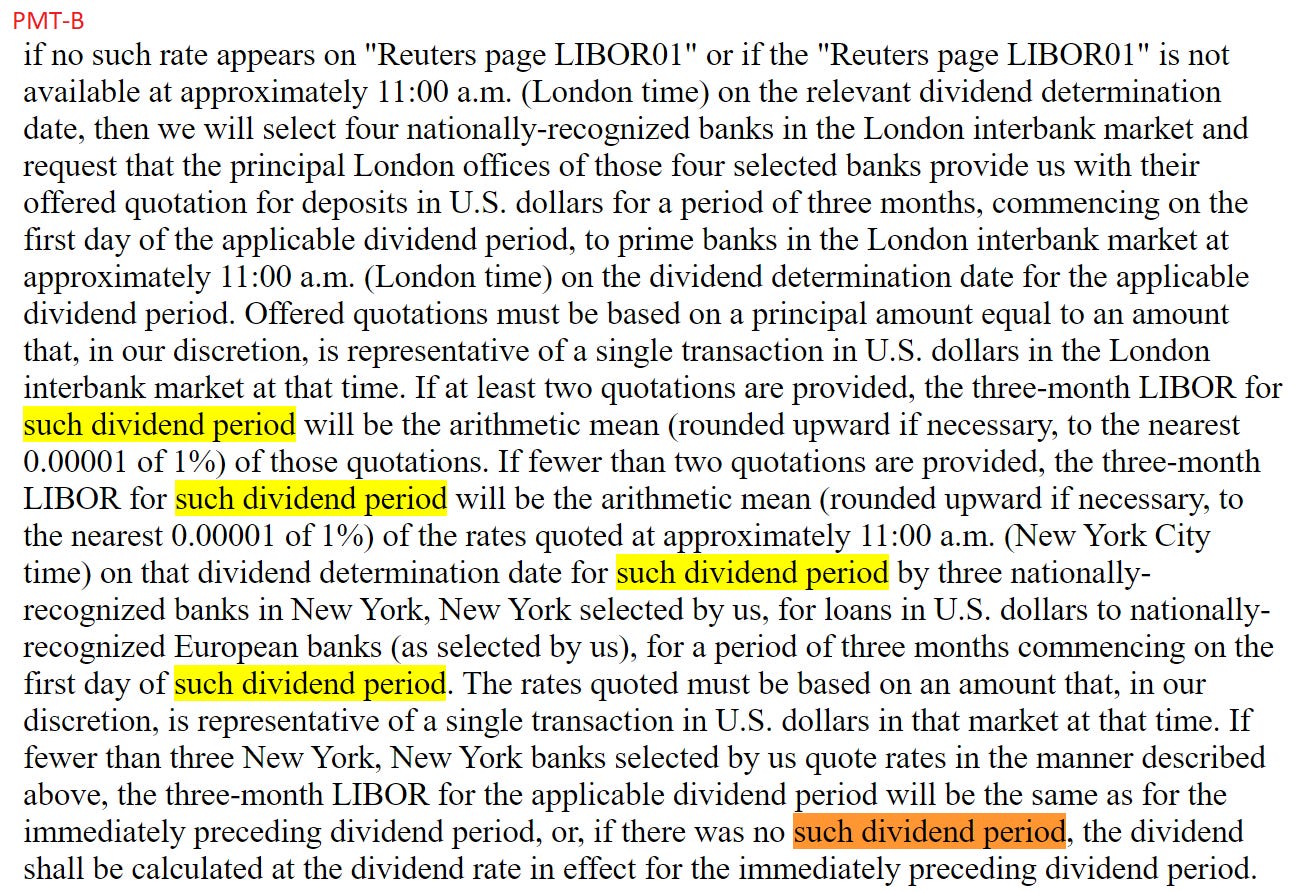

For PMT-B:

There is a minor difference in dates and words (“excluding” vs. “not including”), but they are functionally the same clauses.

A dividend period:

- Starts on the dividend payment date.

- Ends immediately before the next dividend payment date.

For CIM-B, dividend payment dates are the 30th day of March, June, September, and December.

For PMT-B (and PMT-A), dividend payment dates are the 15th day of March, June, September, and December.

No Such Dividend Period

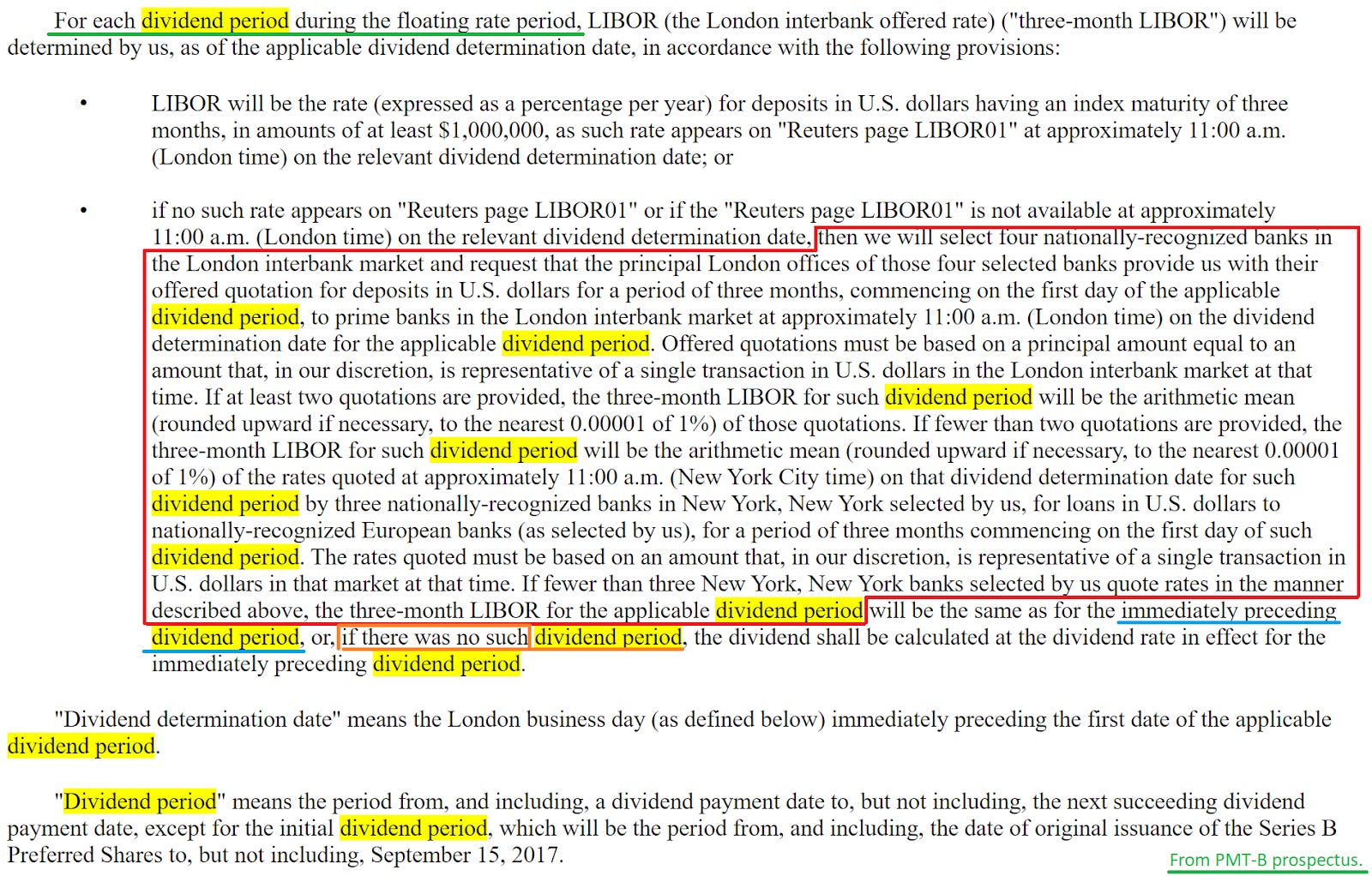

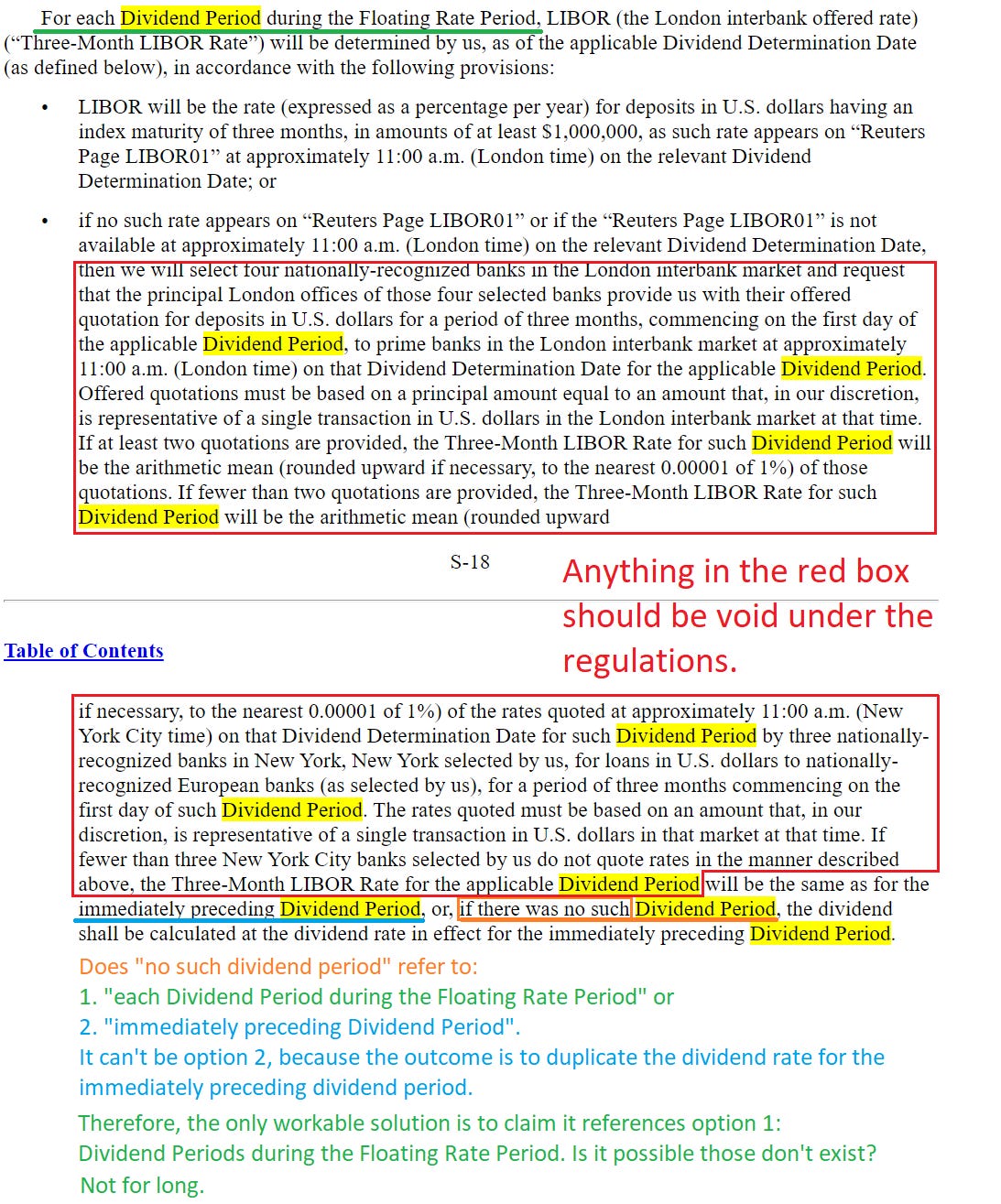

This brings us to the clause about “no such dividend period” (demonstrated below). When I first wrote about PennyMac (PMT) and their preferred share stunt, I argued that the clause “no such dividend period” couldn’t be triggered because every dividend period must exist.

However, that feels strange. Why did they create a clause that could never be triggered?

I couldn’t come up with an answer, so I went looking for other ways to interpret it.

This is the section from the PMT-B prospectus:

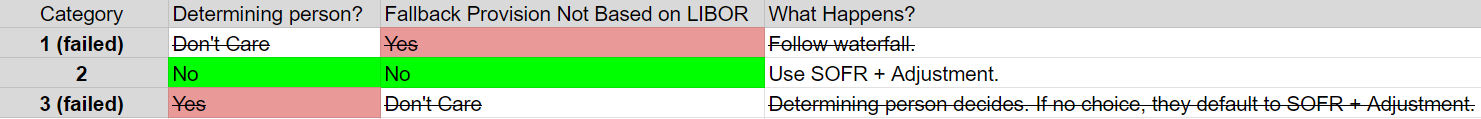

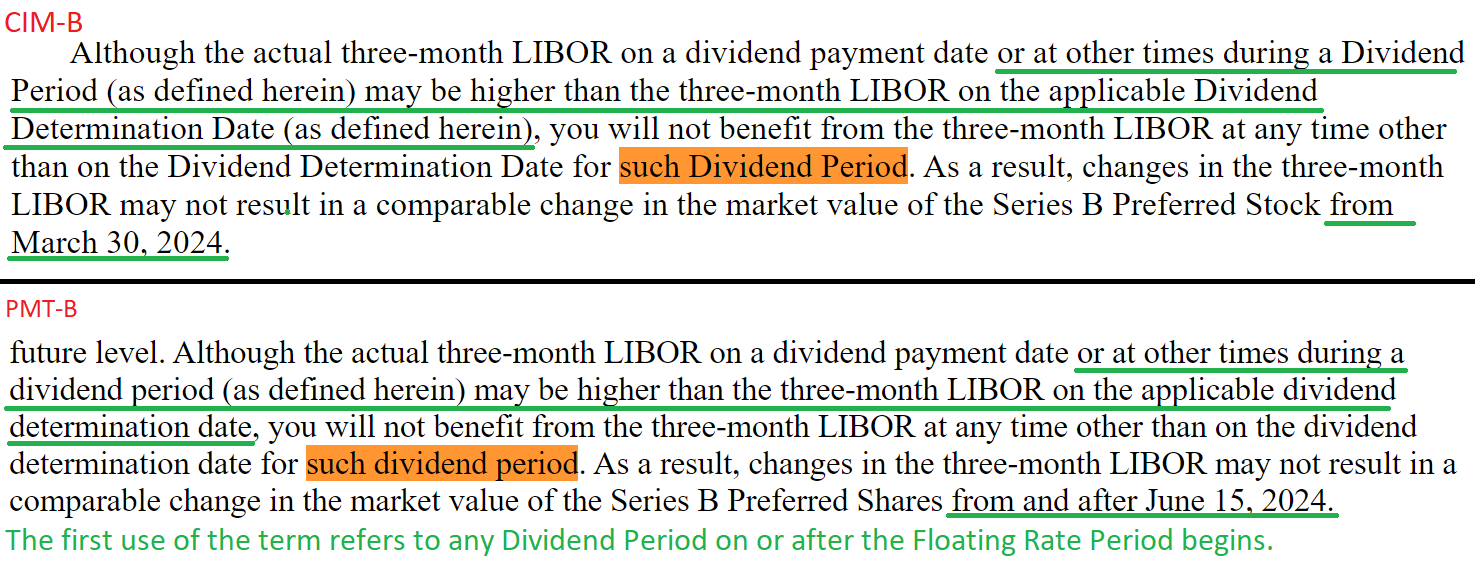

It looks very similar to the section from CIM-B’s prospectus. So we’re going to include that also and add some notes to it. Here is the section from CIM-B’s prospectus:

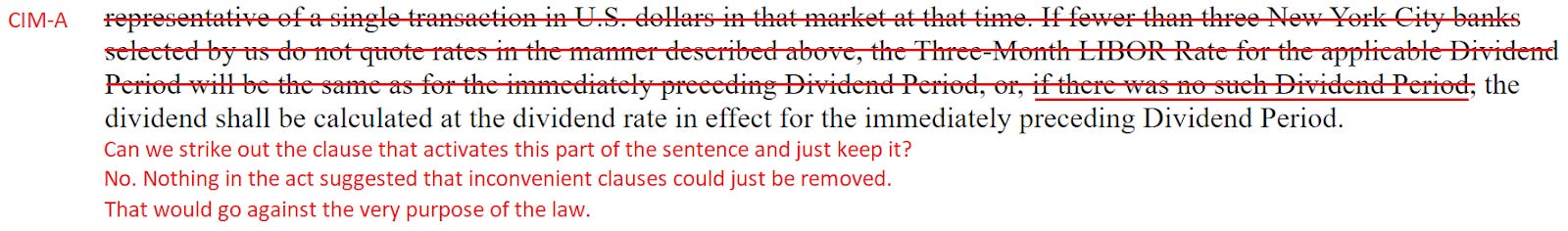

First, we remove everything in the red box. Then, we are left with only two periods it might reference. Neither works.

Option 1: It can’t be the immediately preceding dividend period. We can’t say:

“If there was no immediately preceding dividend period, use the rate for the immediately preceding dividend period”.

That clearly would not be practicable, and the Federal Reserve explicitly required benchmarks to be practicable.

Option 2:

We would have to use the “Floating Rate Period”. We would have to say:

“If there was no Dividend Period during the Floating Rate Period, use the dividend rate from the immediately preceding Dividend Period.”

That sentence appears to make sense. However, you may have noticed that “Floating Rate Period” was capitalized. It’s time for another definition.

The prospectus for PMT-B uses “floating rate period” 4 times, but only one use defines the term:

In each case, we see that the “Floating Rate Period” is not defined by the dividend floating. It is defined as periods that start on or after a specific date. For CIM-B, the date is March 30, 2024. For PMT-B, that date is June 15, 2024. For PMT-A, that date is March 15, 2024.

The dividend should float after those dates, but the definition is based on the date.

Putting the Phrase To Work

Let’s insert the date for CIM-B and see how it goes:

“If there was no Dividend Period during the Floating Rate Period (which begins March 30, 2024)”, use the dividend rate from the immediately preceding Dividend Period.”

When could that be true?

For CIM-B:

On March 30, 2024, someone could state: “There was no Dividend Period (yet) during the period of time that begins today”.

A poor argument, to be certain. It would be made on the first day of the Dividend Period, and the clause never references a full “Dividend Period”. The determination is made at 11 AM, which is quite a few hours after the Dividend Period began.

Could you state that there was no MLB season 11 hours after the first game began?

This is weak and should be rejected.

However, it is the only one where the clause could theoretically be activated. Further, it fits the general layout.

This part of the contract is dealing with what happens if they can’t get LIBOR on that morning. Step 1 is to go to the prior LIBOR. But what if there is no prior LIBOR rate because it is the first floating dividend? Then they might say they need one extra quarter to get it figured out.

This is a bad interpretation, but it’s the only one I can find that allows the clause to be activated.

Note: In my opinion, a poorly designed clause is not entitled to have words twisted to create an environment where it could be activated.

For PMT-A, this is March 15, 2024.

For PMT-B, this is June 15, 2024.

The Second Dividend Period

What happens in the next period?

Fast forward to June 15, 2024.

Was there a Dividend Period during the Floating Rate Period?

Yes.

On June 15, 2024, PMT-A shareholders can state (unless shares have been called):

The prior Dividend Period began on March 15, 2024, and ended on June 14, 2024.

Because that statement will be true by the definitions laid out in the prospectus, PMT-A shareholders can also state:

There “was one such” Dividend Period during the Floating Rate Period.

Even if the dividend didn’t actually float, the Floating Rate Period is defined by the date.

Because there “was one such” Dividend Period, the final clause cannot trigger. The final clause would’ve served a purpose. It would’ve given the REIT one extra quarter to find a solution. That’s a fine purpose for a backup clause.

As of June 15, 2024, PMT-A’s final fallback provision will not be practicable. It cannot trigger. Therefore, if PMT-A relied on that clause, then there would be no way to determine the correct rate.

Since they would not have a practicable fallback provision, shares should be classified as Category 2.

Sneaky Temporary Category 1

The REITs could attempt to get Category 1 initially. They might be able to argue that their single-quarter backup provision “could be used”. However, the very next period would throw them into Category 2. I found nothing in the law that would prohibit a contract from changing between categories if the facts change.

Does this guarantee the companies will follow the law? No. Clearly, our society has quite a few lawbreakers.

It’s also possible that a court determines words have different meanings and comes up with an entirely different ruling.

If this were actually the end, then it would result in floating for PMT-A on June 15, 2024, and PMT-B on September 15, 2024 (each 1 dividend period late). However, as I’ll demonstrate further on, I strongly doubt it goes down this way. There are two bold claims I’m going to make:

- I believe PMT-A and PMT-B will float as originally intended.

- I believe they will float on the date that was originally intended.

All Roads Lead to Category 2

Since PMT-A and PMT-B do not have a “practicable” fallback provision that is not based on LIBOR, they don’t meet the criteria for Category 1. Therefore, they must be Category 2 (just like CIM-B):

However, I wanted to be thorough. Why? Because I don’t like negative surprises. So we’re going through other potential arguments.

Other Such Dividend Periods

I’m removing other arguments preemptively.

Another way to look at the clause “no such Dividend Period” is to hunt for uses of “such Dividend Period”. After all, we’re trying to determine if there was or was not “such Dividend Period”. The phrase was used 6 times in the prospectus for CIM-B, PMT-A, and PMT-B.

The first time, it refers to any Dividend Period after the Floating Rate Period begins.

We have already clarified:

- The “Floating Rate Period” depends only on the date, not on whether rates were floating.

- “Dividend Period” refers to the period from one established date to another.

Referencing a “Floating Rate Period” as “such dividend period” results in a dividend period that exists. Therefore, the clause to keep the prior dividend is not triggered.

Here are the other references from CIM-B:

If we use the same logic with PMT-B, we get the same result (because the wording is nearly identical). Each case of “such dividend period” or “applicable dividend period” is nestled within the clauses for quotes and / or relies on LIBOR:

What if We Remove The Clause?

Look, I know this is a downright absurd idea. However, it was advanced by at least one analyst who believes the fixed-rate view is correct.

So what if we just remove the “no such dividend period” clause?

Removing the clause would create a share that remains fixed-rate forever. However, it would be the antithesis of the law’s purpose. Remember the official purpose of the law?

Is removing clauses because they were not activated going to establish a clear and uniform process? Not a chance.

Would it preclude litigation? No. Each party would want to just remove clauses they don’t like.

Would that allow the contract to operate according to the terms? No, it would be overriding the terms.

However, one author for Bloomberg also weighed in. He paraphrased the law down to a few sentences. Then he moved on to paraphrasing how the terms for a bunch of preferred shares work. The description wasn’t accurate to the shares we’re covered. Unfortunately, readers may rely on such information.

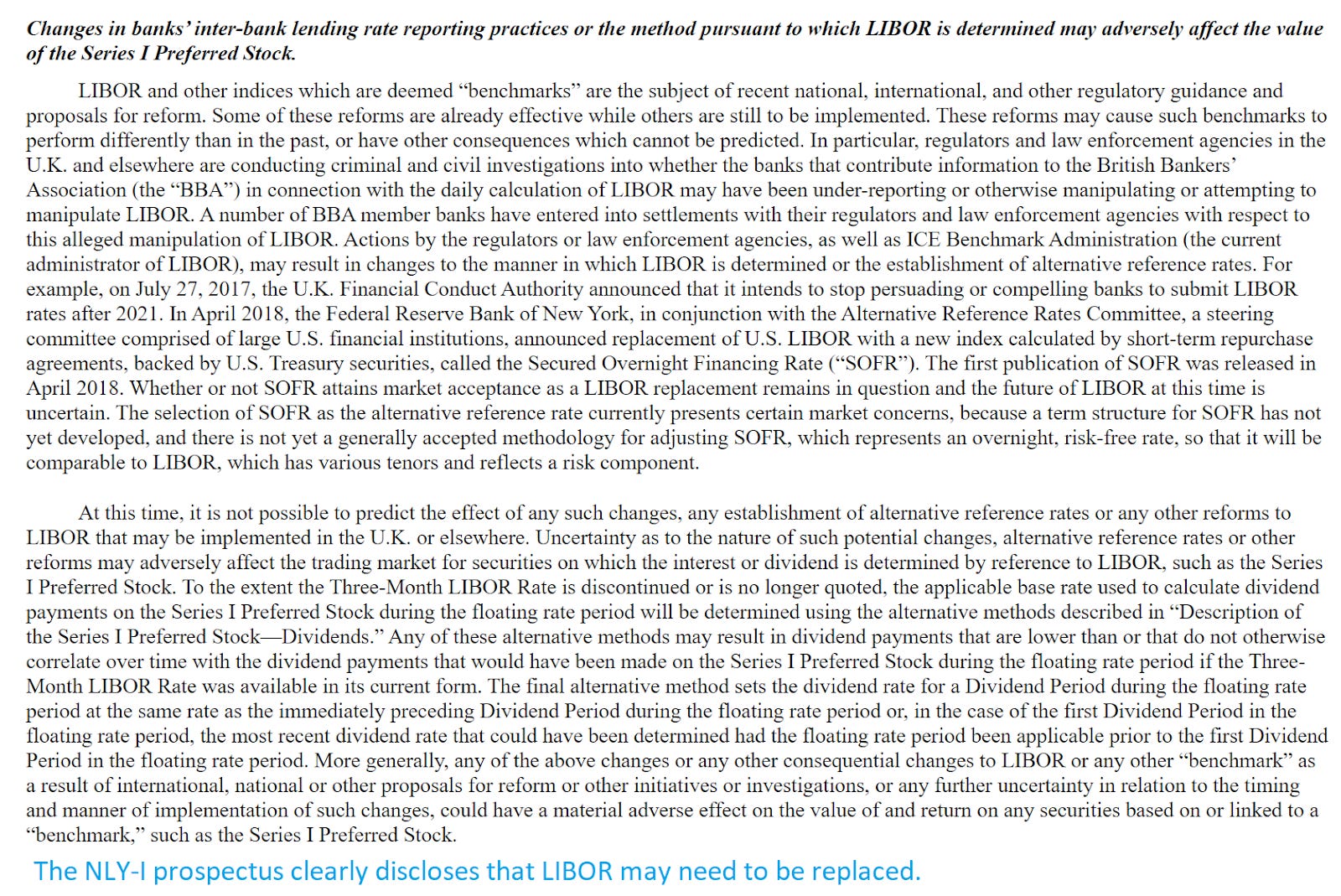

Risk Factors

Companies are expected to disclose the relevant risk factors in the prospectus. If the company views the end of LIBOR as a potential risk, then disclosure is important. Disclosure can protect them from claims.

This is what it looked like when Annaly Capital Management foresaw the potential end of LIBOR while issuing their Series I preferred shares: NLY-I (NLY.PI) (NLY.PR.I):

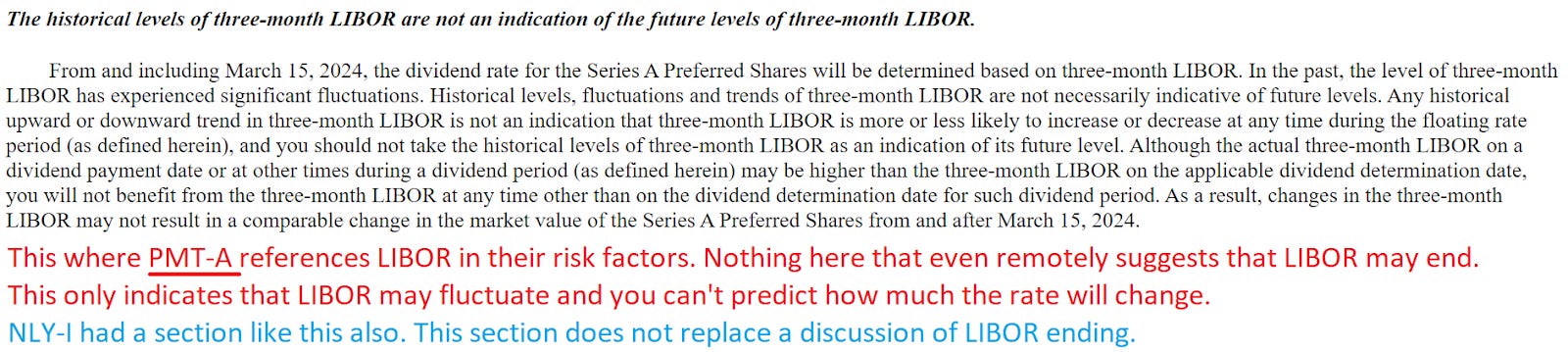

Compare that to the section for PMT-A:

The section in the PMT-B prospectus is extremely similar to the PMT-A prospectus. It does not reference LIBOR ending. Therefore, it is reasonable to believe the contract was not intended to cover LIBOR ending.

Defeat Even in Category 1

Let us assume for a moment that PMT achieves the nearly impossible. They successfully prove that their shares are actually Category 1. Against all odds, they pull it off (because no one shows up to contest their decisions).

If PMT-A and PMT-B are Category 1, can they use the fixed rate? No.

Now, you might be wondering why on earth you dealt with several thousand words only to find out that PMT would actually lose in all scenarios. I can’t answer that for you.

What I can do is show you how PMT still loses.

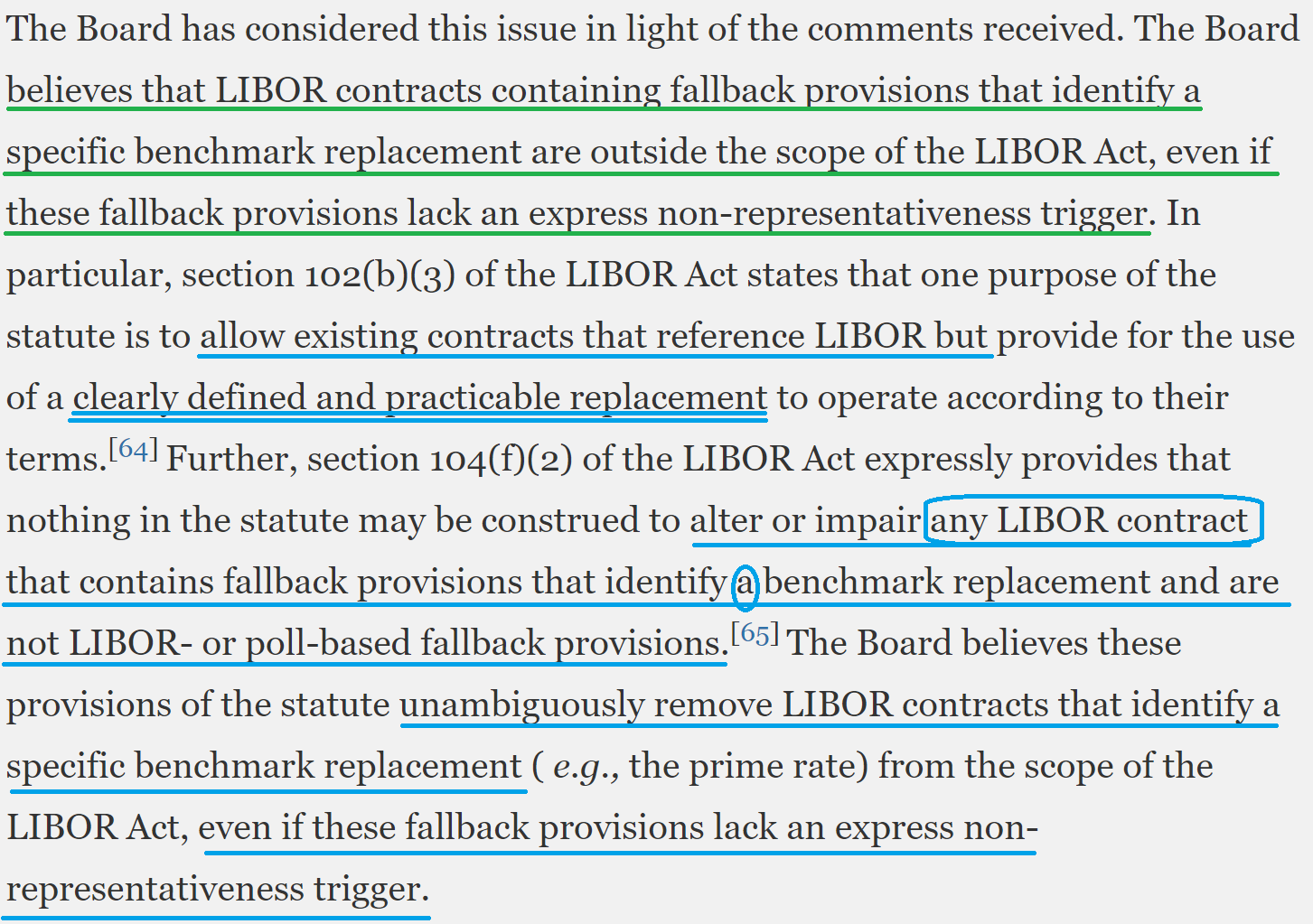

Clarifications By The Federal Reserve

The Federal Reserve provided several clarifications in response to public commentary about the law. One of them is particularly relevant; it refers to Category 1. Since the outcome for Category 1 is simply “follow the waterfall”, the rule doesn’t do much to those shares.

Expanding Category 1

The table I used for the categories was simplified a little bit. The Federal Reserve’s description is actually pretty awful:

Not the best display of English, but we’ve got it down to two options, and only one of them gives any leeway for PMT. We’re pretending PMT-A and PMT-B qualify as Category 1, so we don’t want to spoil the mood.

Outside the Scope of the Act

There was a very particular issue that the board received many comments on. Before revealing what that issue was, I want readers to focus on the board’s answer.

This answer was a surprise to me because it is essentially redefining Category 1. Instead of Category 1 being “Follow the waterfall because we said so”, it means “Follow the waterfall because your contract is excluded”.

This is actually a big statement. The interpretation by the Federal Reserve comes out like this:

“If a contract contains “a” (at least 1) clearly defined and practicable benchmark replacement (interest rate or dividend rate), then… the contract may not be altered or impaired. That contract falls outside the scope of the act. Follow the terms.”

So why did the Federal Reserve Board need to provide that answer? What topic could possibly have prompted that?

Synthetic LIBOR

Remember how LIBOR was going away? What if it didn’t actually go away?

While the United States was doing away with LIBOR, other agencies wanted LIBOR to last a bit longer. Consequently, something called “synthetic LIBOR” was created.

What is synthetic LIBOR? It’s similar to LIBOR, but not actually LIBOR. Well, that depends on who is writing the word “LIBOR”. It’s not LIBOR under the law, but it may still be LIBOR within the contract.

Synthetic LIBOR Comments

There were several opinions on how the board should handle synthetic LIBOR. The following section highlights those suggestions and how the Federal Reserve responded.

These suggestions demonstrate that the Federal Reserve Board knew exactly what they were doing. They refused to eliminate synthetic LIBOR. Let the fun begin.

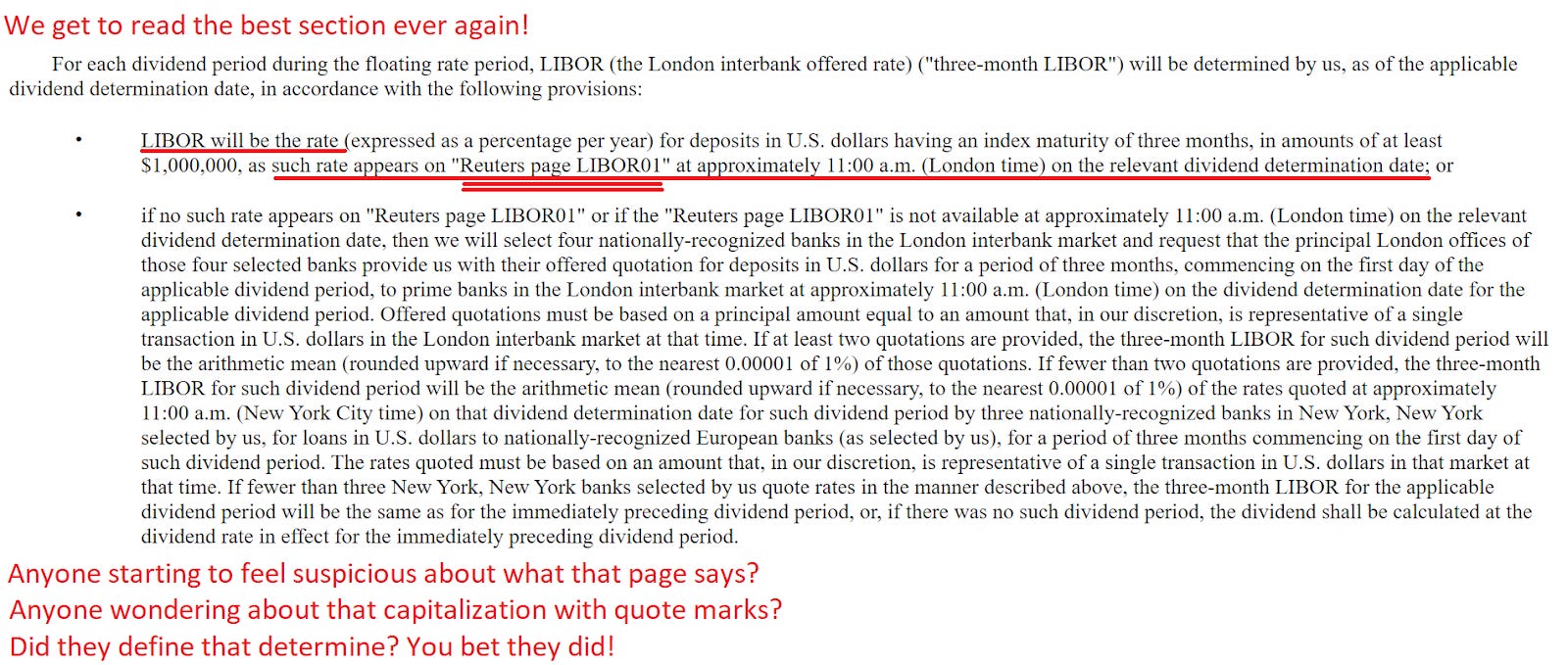

How Did PMT Define LIBOR?

We return to a section we’ve posted several times before. But now we’re coming with new information. If these shares are Category 1, the Federal Reserve Board says the LIBOR Act won’t apply. That changes things. If the LIBOR Act doesn’t apply, then this first clause is still live:

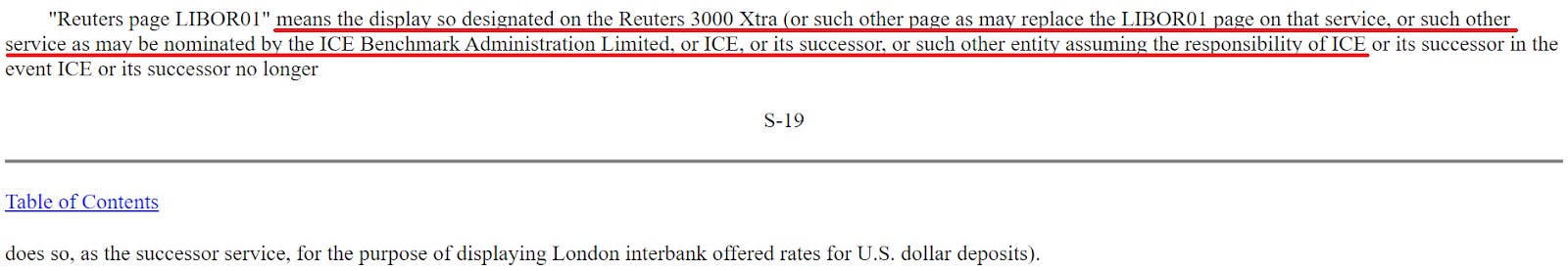

Could we get a definition for where we should look?

That’s a very specific location. We’re looking for Reuters 3000 Xtra or such service as may replace it.

Can you feel what’s coming? The other shoe is about to drop.

The Reuters 3000 Xtra no longer exists. It was decommissioned in 2013 and replaced with the Eikon. As the CEO of Thomson Reuters said on June 26, 2013:

“We want to replace Xtra 3000 as quickly as we can because Eikon sticks a lot better.”

PMT-A’s original issuance date was expected to be March 9, 2017. For PMT-B, it was expected to be July 5, 2017.

Why was a tool that was defunct for years used in the boilerplate text? Good question, but it doesn’t matter.

The Shoe Drops

The successor was the Eikon. That was known years before the prospectus was written. Therefore, the terms had to be referencing the Eikon. The Eikon still exists. If PMT-A and PMT-B are Category 1, they are required by law to follow their waterfall.

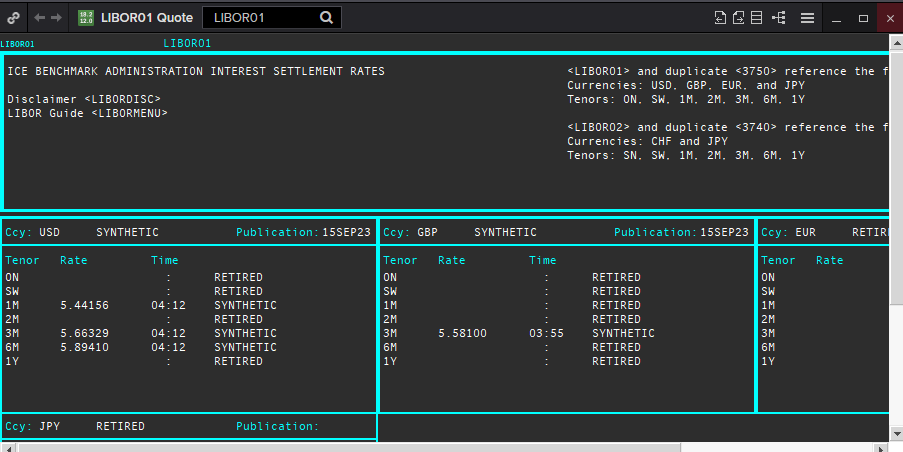

What will happen when they log onto an Eikon and go to that page they very specifically referenced in their contract? The one called “LIBOR01”?

They will find ICE is using that page to post 3-month synthetic LIBOR:

Note the "publication"; it's just a little left of center. "15SEP23". That's the date of the publication. September 15, 2023. Months after LIBOR was officially dead. Note the status: "Synthetic". If PMT gets classified as Category 1, this is what they get.

Will that still exist on March 15, 2024, and June 15, 2024?

Yes, it will. The Financial Conduct Authority announced that “3-month synthetic LIBOR” will exist until September 30, 2024.

Someone at PMT is going to be very angry when they realize that they pulled this stunt for nothing. Even if they could get classified as Category 1, they would be forced to accept synthetic 3-month LIBOR.

To be clear, if PMT tries to pay a fixed-rate dividend, it isn’t all that much work for someone to pull up an Eikon and point to the correct rate.

Legal Experience

PMT has encountered judges before. They were already accused in a different class action case. The lawyers suing PMT posted about it on their website.

“After the case was filed, PennyMac attempted to obtain releases from a number of employees under false pretenses by claiming that the employees would receive nothing if Smigelski won the case. This was not true. Accordingly, the Sacramento Superior Court invalidated the releases, explaining: “the California Supreme Court has made clear that the penalties go not only to the citizen bringing the suit but to all employees affected by the Labor Code violation.” The Court also required PennyMac “to submit for the Court’s approval any future proposed settlement of the PAGA claims identified in Plaintiff’s complaint.”

The Superior Court also required PennyMac to send a corrective notice to all employees who signed one of the invalid release agreements, informing them that the releases are invalid.”

I’m not a lawyer. So this is just my view. It seems like when a company pursues employees to get released from claims, then has a court invalidate the releases, that’s probably bad. When the court requires the company to submit any future settlements to the court for approval, that also reflects poorly on its legal team.

I’m inclined to think CIM got this right, and PMT is just wrong. Again.

Pricing (as of 10/05/2023, initial subscriber release)

- PMT-A closed at $20.87.

- PMT-B closed at $20.09.

- PMT-C closed at $17.05.

PMT-B’s yield is higher than the yield on PMT-C. That makes sense if the market believes PMT-A and PMT-B will never float. If the market believes that, it would favor PMT-C for greater upside if interest rates fall at some point.

I think the market is believing PMT. It shouldn’t, but who digs this deep? The market was quite surprised when the announcement came out that CIM-B would float, as CIM confirmed it should under the law. I was not surprised. We were still predicting CIM-B would probably float without any negative announcements (trying to claim it was fixed-rate before losing).

Conclusion

PMT’s only hope is to avoid any competent judge or regulator from looking at this situation. That seems like a stretch, given the amount of attention this issue will get over the next month. In PMT’s press release, they failed to provide any remotely adequate explanation for their decision. That makes sense if they didn’t want to be committed to only one of the bad defenses they have available.

It’s a viable strategy to exhaust opponents. Because they didn’t provide enough details, I had to spend much longer disproving every potential claim. That is the cost of accuracy.

I may open a position in PMT-A or increase my position in PMT-B. I believe the following things:

- They will float regardless of what PMT wants.

- They will begin floating on the initial floating date.

- PMT will face significantly more pressure as this goes public.

- Shares should be classified as Category 2.

- If they pull off an upset and achieve Category 1, synthetic LIBOR will force the first dividends to float.

- There is no argument where the first dividend floats, followed by a return to the original rate.

Disclosure: Long all stocks in CWMF’s Portfolio. Our portfolio can be accessed at any time from the Google Sheets page.

Secondary Disclosure: Since this is for the public release and the Google Sheets page is only available to paid members, as of 11/16/2023, I am long the following shares:

RITM-D, GPMT-A, DX-C, EFC-A, MFA-C, RITM-C, EFC-B, PMT-C, PMT-B, CIM-B, AGNCP, CIM-D, RITM, SLRC, MFA, GPMT, RC

I actively trade between positions, so those positions may change at any time.

Where else do you find research like this? Get 3 friends to sign up for our free e-mails and you’ll get a complimentary month of premium access.

Member discussion