Higher Interest Rates And Popular Lies

Note: This article was previously sent to subscribers on our REIT Forum platform through Seeking Alpha. I could post it to Seeking Alpha’s “public” side, but it would still get hit with a paywall. To allow all readers to see it, I’m sharing it as a public article here. If you’re not yet subscribed for free alerts from our site, you can sign up here:

The entire article is split into 3 parts because there are natural breaks and Gmail limits e-mails to 102KB. This is Part 1. Part 2 and 3 will also be published here. Part 1 and 2 lay the foundation while part 3 brings it all together.

Summary of Series (includes Parts 1, 2, and 3)

- The Federal Reserve has talented economists. However, they have relied upon facts which were later proven to be definitively false. (Part 1)

- Evidence from the 1980s demonstrates inflation was actually driven by cost of production. The Federal Reserve raised rates and inflation declined, but correlation is not causation. (Part 2)

- Today we are seeing a similar situation in the cost of production. Supply has been reduced, driving prices higher. Higher interest rates reduce production, rather than increase it. Bad solution. (Part 3)

- The free market is already working to reduce inflation. By raising rates as the market works, the Federal Reserve can yet again claim victory for a battle they didn’t fight. (Part 3)

- This policy has the potential to create a recession, reduce output, spur trillions of additional deficit spending, and drive billions in net interest income to Bank of America. (Part 3)

Can we be real about economics for a moment?

There are a few common misconceptions that should be addressed. This article may challenge some of your beliefs. For most people, considering an alternative point of view is a difficult task. The things I’m going to say run contrary to a narrative that has been pushed for decades and accepted by most people.

To warm investors up to accepting new ideas, I’m going to start with two popular ideas which have been disproven by an abundance of evidence. Then we’ll tackle the myth that is still widely believed.

Note: To focus on market prices and avoid the delay in reporting changes in market rents, we will be using a version of CPI (Consumer Price Index) that explicitly excludes “shelter” from the calculations. Therefore, all references to CPI in this article will refer to this modified value.

When Economists Make Mistakes

No field is perfect. Mistakes happen. It shouldn’t be surprising that sometimes conventional wisdom is proven wrong. For instance, it was common knowledge that increasing the money supply created inflation. I want to highlight comments from the Federal Reserve, made in a presentation at the Cass Business School in London on March 24th, 2009:

“There is a variety of practical policy tools that a central bank can employ when the zero bound on nominal interest rates precludes additional rate cuts. In particular, the zero bound does not prevent a central bank from taking actions that increase the growth of the monetary aggregates. It is well known and widely understood that, over the medium to long run, inflation reflects the growth rate of money. The current environment of exceptionally low short-term nominal interest rates does not prevent a central bank from increasing the money supply. In this sense, stabilization policy goals can be accomplished through influence on the expected rate of inflation.”

In that one paragraph, this member of the Federal Reserve clearly demonstrated two beliefs which are now demonstrably false:

- The zero bound on nominal interest rates precludes additional rate cuts. This meant that interest rates could not be less than 0%. It was widely believed.

- Over the medium to long run, inflation reflects the growth rate of money.

Before I prove those statements wrong, we need to evaluate what the speaker meant by the “growth rate of money”. Fortunately, we’re able to do that because he went on to say:

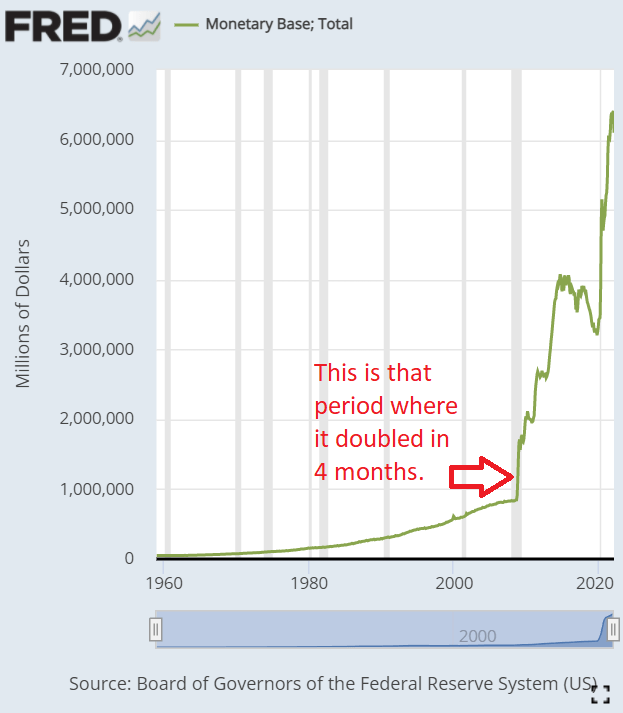

“The monetary base consists of currency in circulation and the deposits of banks and other depository institutions with the central bank. In the United States, the size of the monetary base doubled over a four-month period beginning in September 2008.”

That quote is important for two reasons:

- The term “monetary base” has a specific meaning.

- We can verify that our chosen value of “Monetary Base; Total” doubled during that 4 month period. This confirms that we have the same definition.

Now that we have assigned clear definitions, we can proceed to prove those statements wrong.

Zero Bound on Nominal Interest Rates

The Federal Reserve stated that the zero bound would “preclude” additional rate cuts. Let’s avoid any confusion about what it means to preclude something:

There can be no doubt that the Federal Reserve stated further rate cuts were impossible.

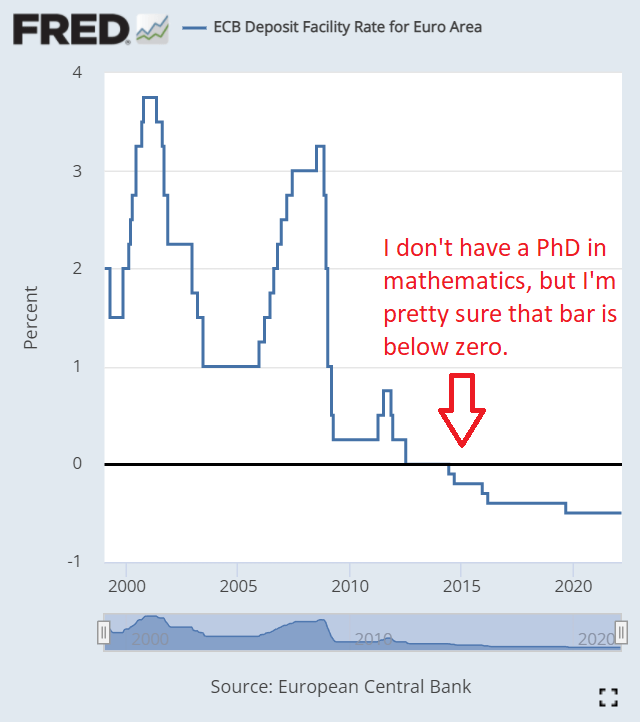

That theory is in the dumpster fire of history:

For about 8 years the nominal rate for the ECB (European Central Bank) has been negative. So perhaps instead of “impossible”, it should’ve been “inevitable”?

The Monetary Base

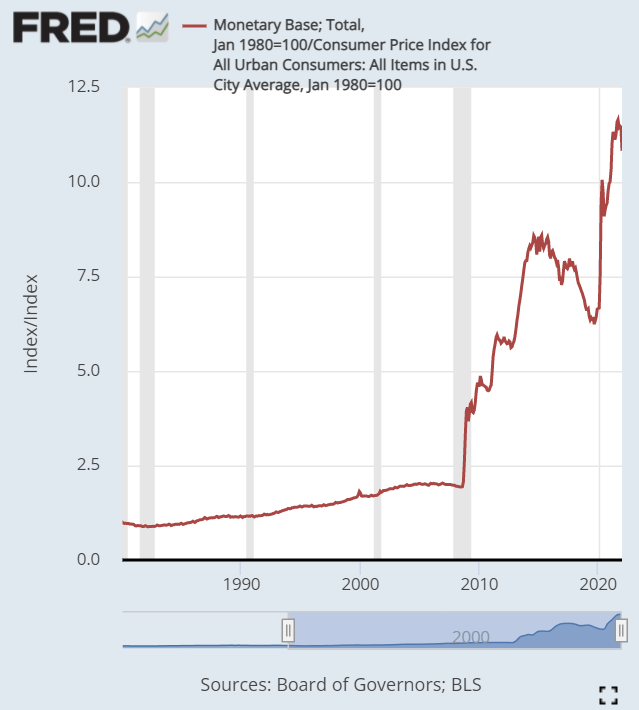

To disprove the second claim (that a large monetary base causes inflation), we’re going to start by demonstrating the monetary base:

We can see that this is the right metric in two ways:

- It’s called “Monetary Base; Total”

- It doubled at precisely the right time.

According to the speech:

“It is well known and widely understood that, over the medium to long run, inflation reflects the growth rate of money”.

It may have been “well known” and “widely understood”, but was it true?

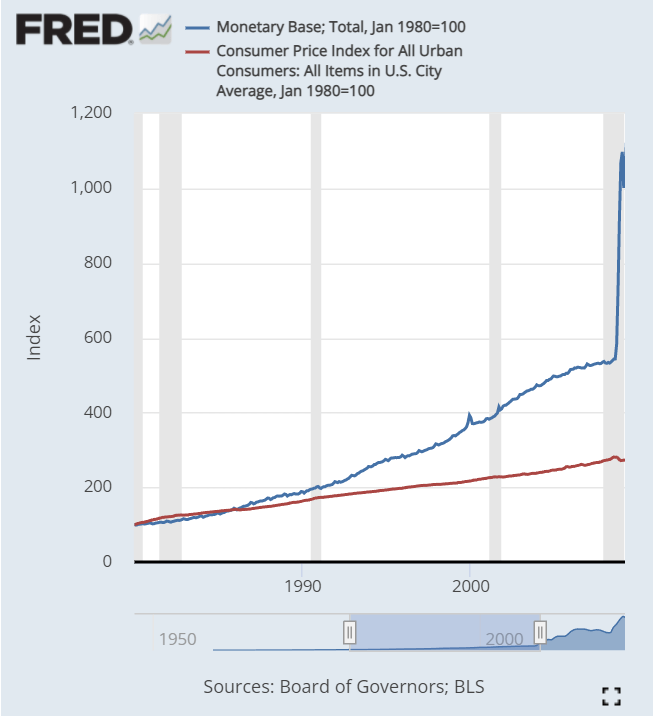

Prior to his speech, the connection was pretty weak:

From 1990 to 2009, both values increased. However, they increased at substantially different rates. Regardless, they were both consistently trending upwards, even if those growth rates were materially different.

Let’s try making two adjustments to the chart:

- We will zoom out to include more recent data.

- We will create a ratio between the two metrics.

Since we indexed both metrics to their value from the start of 1980, a ratio gives us a reasonable way to get a rough feel for how things changed over time.

If growth in the “monetary base” actually created inflation, the ratio wouldn’t have been able to increase so dramatically. We have seen “some” inflation, but it didn’t come remotely close to the increase in the monetary base. Not in the same ballpark. Not in the same city. A larger monetary base absolutely did not cause inflation.

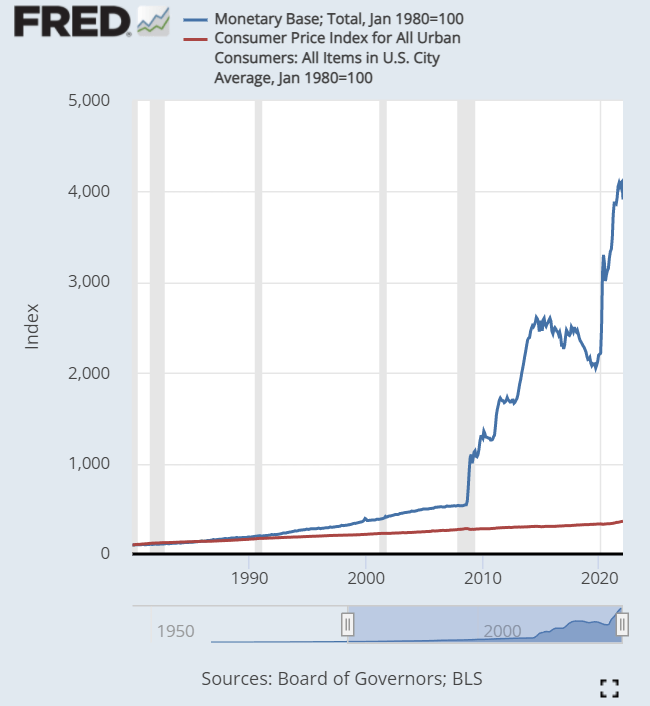

Want to see what the values look like if we don’t turn them into a ratio? The chart below shows you the growth in CPI along with the growth in the monetary base:

Even if we believe the CPI is underreporting inflation, no reasonable argument can be made for inflation growing near the rate of the monetary base. Not today. That argument was accepted in 2009, but subsequent evidence invalidated the theory.

Causation

It would’ve been fair to suggest that a larger monetary base historically correlated with inflation. The amount of correlation changes over time, but I think it would be wise to remove the “causation” label. Why didn’t increasing the monetary base create inflation? Because most of the “new money” wasn’t actually going into the economy. If the money isn’t being spent, it doesn’t drive inflation.

Recap For Part 1

The Federal Reserve employs experienced economists. About 13 years ago, they were taking for granted things that have since been proven completely false. They considered those points to be so obvious that they could be laid down as the foundation for building further arguments.

It was previously believed that nominal interest rates could not go below zero, but it is obvious that they can. It’s happened for the last 8 years. Every single day. This is not an isolated event. This is the new normal.

We’ve also proven that growth in the monetary base, even if it is maintained for years, failed to create inflation. While some inflation did occur, it was minimal compared to the increase in the monetary base.

Now we can confidently say that even widely accepted theories can be proven wrong.

We will build on these concepts in Part 2 and Part 3.

Member discussion