Higher Interest Rates And Popular Lies (Part 3)

This is part 3 of our series “Higher Interest Rates and Popular Lies”.

You can click here for part 1 or click here for part 2.

As a reminder, the main points of the series are as follows:

Summary of Series (includes Parts 1, 2, and 3)

- The Federal Reserve has talented economists. However, they have relied upon facts which were later proven to be definitively false. (Part 1)

- Evidence from the 1980s demonstrates inflation was actually driven by cost of production. The Federal Reserve raised rates and inflation declined, but correlation is not causation. (Part 2)

- Today we are seeing a similar situation in the cost of production. Supply has been reduced, driving prices higher. Higher interest rates reduce production, rather than increase it. Bad solution. (Part 3)

- The free market is already working to reduce inflation. By raising rates as the market works, the Federal Reserve can yet again claim victory for a battle they didn’t fight. (Part 3)

- This policy has the potential to create a recession, reduce output, spur trillions of additional deficit spending, and drive billions in net interest income to Bank of America. (Part 3)

Part 3

The Recession Impact

So far, we focused on two factors that contribute significantly to supply. When we consider how quickly the rate of inflation declined, we should also consider changes in demand. Remember, there were two recessions in this period and recessions generally involve an increased unemployment rate.

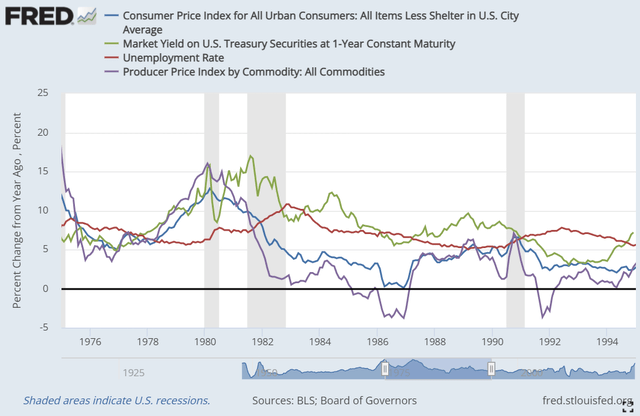

The next chart is going to combine four factors:

- The change in CPI excluding shelter.

- The market yield for the U.S. Treasuries with a 1-year maturity.

- The unemployment rate

- The producer price index for all commodities

As before, I’ll start with the chart and then I’ll provide it again with commentary:

It’s pretty clear in that chart that the change in PPI is the leading factor. However, we may also figure that increased unemployment is driving down prices. There’s less demand for goods and services combined with a greater supply of available labor. That combination brings demand down dramatically.

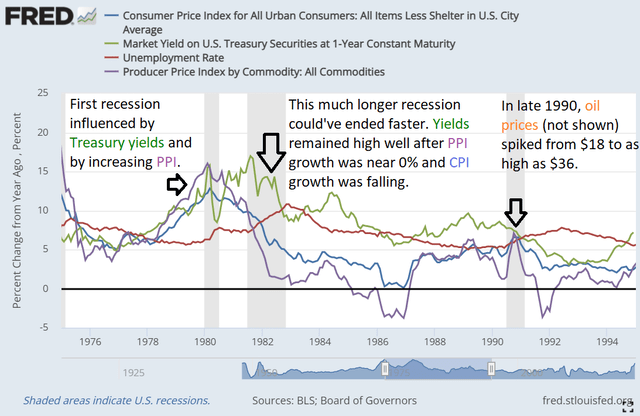

When I look at the chart, I see rising yields and increasing PPI creating a problem, but it was the second dip where things got bad:

The free market was already solving inflation in late 1981. You can easily see:

- The leading indicator, growth rate in PPI, was falling rapidly.

- The growth rate in CPI was already following the PPI lower.

Therefore, hiking interest rates was not necessary. Hiking rates did not materially reduce the growth rate in PPI. Stable oil prices did.

That recession showing up in the second half of 1990? That was oil prices going from $18 to $36. The shock to oil prices meant a higher PPI and reduced the cash consumers had left to spend on other goods and services. What caused the 1990 oil price spike? Iraq invaded Kuwait and knocked out two of the world’s biggest oil producers. That’s your recession, yet again, triggered by a sudden surge in the price of oil.

Applying The Wisdom Today

Today, we are hearing that inflation is coming from the increased monetary base. In the first part of the article, we demonstrated that the monetary base simply does not have much power to cause inflation. Despite the monetary base increasing dramatically, we did not have meaningful inflation until consumers were met with a sharp decrease in supply.

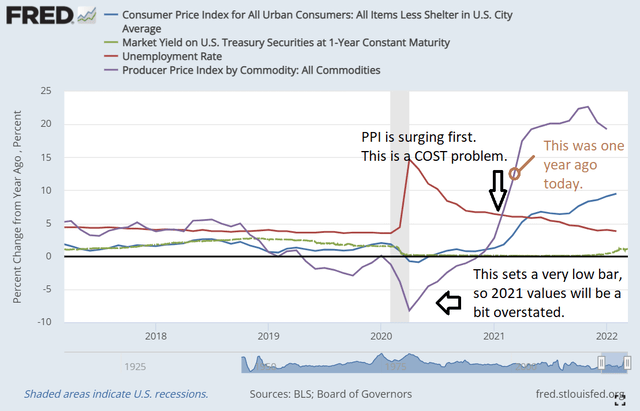

The “answer” being promoted is to increase interest rates substantially. We are told that “higher rates solved inflation” in the 1980s, but that’s simply not true. Stabilizing oil prices, a key factor in supply, solved inflation. Much like today, the inflation of the 1980s was driven by increased costs of production. If we’re right, we should expect the PPI to jump a bit before the change in CPI. The PPI increased first because the cost of production was increasing. Then it was followed by higher costs for consumers:

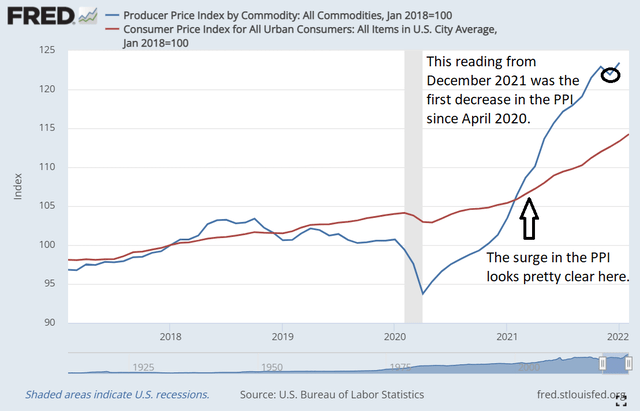

The magnitude of the jump in the PPI is overstated because of the comparison period. However, we can see that it did clearly increase first. To solve for that issue in the year-over-year comparison, we can simply draw a new chart where we measure CPI and PPI relative to January 2018:

While the PPI is not “falling”, the figure was stabilizing in late 2021. If the PPI remained roughly unchanged over the next year (less likely now given the oil shock), it would be reasonable to expect the growth rate in CPI to be resolved over the next year or two.

Excessive Demand

We’ve covered the typical factors, but this time there is another factor. You may have heard some mentions of the federal deficit? We have two political parties and both like running a deficit. We’re not handing out free passes to any political party.

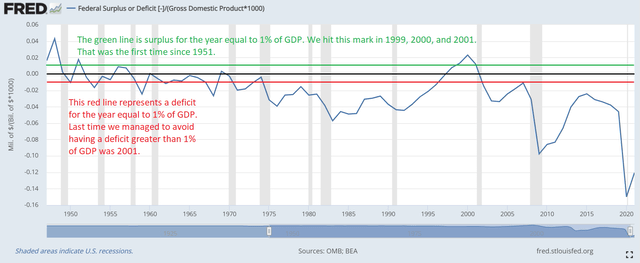

To eliminate issues with inflation and the growth of the economy, we’ll be using the federal deficit divided by GDP. Inflation would’ve impacted both of these figures by the exact same amount. Further, using this ratio allows us to recognize that a larger economy can cover a larger deficit.

The United States ran a surplus larger than 1% of GDP in 1999, 2000, and 2001. Those are the only surpluses greater than 1% since 1951.

We only had a surplus greater than 1% of GDP in 3 years out of the last 80. We also only avoided a deficit greater than 1% of GDP in 5 years out of the last 48. Those were 1997 to 2001. Deficit spending has been a way of life. While lower interest rates make carrying the debt easier, we want to focus on the current period.

A huge deficit in 2020 was a reasonable response to the pandemic. Clearly, it wasn’t a perfect response. We all know that. But the premise of running a deficit during a pandemic is appropriate. Continuing to run a similar deficit into 2021 was excessive. Based on projections from the CBO (Congressional Budget Office), the deficit for 2022 should be about half of the level from 2021. Sure, that’s “a 50% reduction”!

However, it means the 2022 projected deficit relative to GDP would be the largest since 2012. It would compete with 1983 (at 5.718%) for the largest deficit relative to GDP outside of the Global Financial Crisis.

How Deficits Impact Demand

The deficit is a function of government spending exceeding revenues. We previously mentioned the role of demand in creating inflation. Deficit spending creates demand. It creates demand much more effectively than minor changes in interest rates. In 2021, the deficit was around $2.8 trillion. Trillion. That’s a bigger factor than interest rates.

For 2022, the projections call for $1.3 to $1.4 trillion.

The Way to Actually Fight Inflation

The way to handle inflation in this environment is pretty clear:

- Allow the free market to increase productive capacity to meet demand.

- Encourage competition so lower costs reach consumers.

- Stop or dramatically reduce deficit spending as a response to inflation.

These options are not politically feasible as neither party supports them. The first two lead to weakening margins while the third reduces revenues (or increases taxes).

So instead, we’re left with a politically acceptable plan of decrying inflation and telling people the best option is to raise rates. Most companies won’t complain because the impact on their debt costs (with mostly fixed-rate debts) is smaller than the cost of the other options.

However, some companies are pushing hard for higher interest rates.

Pushing for Higher Rates

They are trying to influence public opinion. For instance, Bank of America (BAC) has been pretty vocal in sending their analysts to promote higher rates on news platforms:

“In a Friday analyst note to clients, the Bank of America economists – led by Ethan Harris – projected seven, quarter percentage point rate increases in 2022, putting the target range between 2.75% and 3% at year's end.”

That note wasn’t just sent to subscribers. It was advertised openly across several major news channels. Why would the bank want to give away their valuable predictions? Because they want people to accept higher rates. The more people accept and expect higher rates, the simpler it is for the Federal Reserve to raise rates.

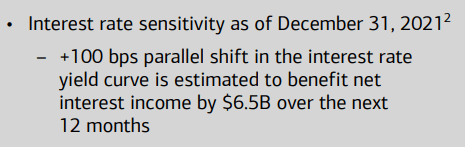

But why does Bank of America care? Perhaps they could explain their viewpoint on page 12 of their investor presentation?

Right, if your bank stands to earn an extra $6.5 billion in net interest income per year from rates moving up by 100 basis points (that’s 1.00% in absolute terms), that would be a pretty big incentive. They are pushing for a 175 basis increase.

For comparison, the net interest income for Bank of America in 2021 was about $43 billion.

Yesterday, CNN joined in by providing an article on the importance of raising rates. That piece hilariously even claimed that higher rates mean you get paid more on your savings account. Remember the years prior to the pandemic? My banks did not materially increase the rate they paid on cash. How about yours? If you had to change banks or make any active adjustment to get the higher rates, that doesn’t count. That’s a promotional activity disguised as paying interest.

Recap For Part 3

The PPI (Producer Price Index) is a useful tool for understanding the CPI (Consumer Price Index). Growth in the cost of production fuels inflation because companies wouldn’t continue to produce products if they sold for less than the cost to produce them. In the 1970s and 1980s, it was the cost of oil driving inflation. When the cost stabilized after price controls were removed, the rate of inflation began falling rapidly.

The Federal Reserve raised rates at the same time and took historical credit for their brilliance. Realistically, the Federal Reserve had a relatively small impact on inflation when compared to the other market forces. Most of the impact they did achieve was a result of driving unemployment.

They are preparing for another series of hikes. These hikes will lead to claiming victory over inflation. If the Federal Reserve did relatively little, the inflation would still taper off over the next two years.

If the actual goal was to reduce inflation, there are other methods that are far more effective. Those methods are not politically acceptable and neither party will seriously fight for them. Having the Federal Reserve raise rates is politically acceptable and it appeases some major banks. Therefore, that is the method we should expect. From the Federal Reserve’s perspective, it doesn’t matter that raising rates is a poor tool for fighting inflation. It’s the only tool they have and they can celebrate their brilliance after using it.

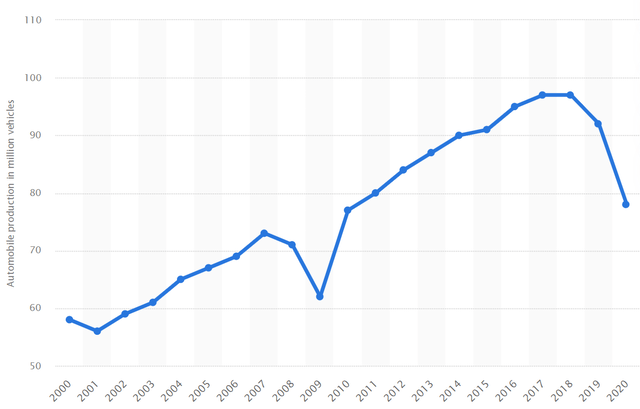

Supply Issues?

We’ve made a strong case already that inflation is being driven by an imbalance between supply and demand, rather than by low-interest rates. However, we want to hammer that point home just a little harder. Some prices increased more than others. One of the largest increases was in the cost of vehicles. Consider what happened with vehicle production. This is the chart for estimated worldwide motor vehicle production (not sales) from 2000 to 2020:

Source: Statista.com

Notice a problem? Will higher interest rates increase supply? No. For higher rates to lower prices, the higher rates need to be removing potential buyers from the pool either by making financing too expensive or making those buyers too unemployed. That’s not a solution. That doesn’t solve anything.

Increasing unemployment (by creating a recession) reduces the production of other goods and services. When the problem is a lack of supply, increasing unemployment compounds the issue. Consequently, the actions planned by the Federal Reserve represent the worst path available.

The Federal Reserve is preparing to create a recession to fight inflation driven more by low supply, rather than by strong demand. Lower supply could be offset by lower demand, but demand is being artificially elevated by aggressive deficit spending. To fight the recession, we may see larger deficits maintained. The result is a combination of:

- Higher unemployment

- Lower output (due to fewer working people)

- Huge increases in federal debt

- Inflation decreasing at about the same rate it would’ve decreased anyway as other bottlenecks in the supply chain get resolved by the free market

Conclusion

There are several things investors should expect. The groundwork has already been laid and the public perception is in place. Here are some things to expect:

- Short-term rates will be increased multiple times (as the bond market already predicts).

- The rate of inflation will come down over the next few years because supply constraints are not getting worse and the deficits will trend lower over the next few years.

- Higher rent removing spending money from consumers will also reduce aggregate demand for goods and services, contributing to slower inflation.

- The Federal Reserve will claim credit for stopping inflation and attribute it to their brilliant decision-making. Very few investors will recognize the truth.

- Bank of America will attribute the increase in net interest income to excellent management worthy of significant bonuses.

- News outlets will publish content prepared for them by other sources because it produces revenue with no expense. This content will most likely praise the higher rates.

Member discussion